Excerpt from:

Excerpt from:Reluctant Revolutionary:

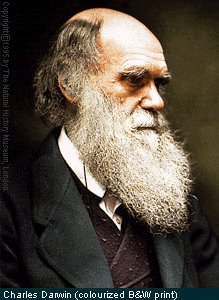

Charles Darwin and the Theory of Evolution

June 2000

by Gerald Gabriel

The Man Lionized

As difficult as it all was for Charles Darwin, the fact is that no one could have pulled it off as well or as easily. No lesser a scientist, nor royal dilettante, nor perfectly accomplished man from a lesser social class could have demanded the ear of so many. Darwin's independent wealth made him that much more secure from such reprisals as a firing, which many a radical thinker had been handed in those times.

Because of his life's arduous work in nearly every imaginable area of the sciences, nobody could discount him—as other evolutionists were discounted—for a lack of credentials or expertise or for dubious political motivations; as a rule he avoided politics altogether. He had to be dealt with, then, and when people began to examine the evidence, the turn toward Darwinism, initially a slow trickle, became a torrent in less than ten years. Even those who couldn't bring themselves to accept Darwin's evolution—what he called "natural selection"—were forced to admit that there was something to the theory.

When he was pushed into publishing his ideas by Alfred Russel Wallace, who had independently come up with very similar views, Darwin was fifty years old. He had been battling illness for twenty years, and didn't expect to live much longer (though he would, for almost another quarter century). He hardly ever left his home by fifty, turning down all manner of invitations and award ceremonies. But he became a sort of living landmark in the years after the publication of The Origin of Species, (1859) and people—scientists, mainly, but others too—would journey to his backwater home, in Downe, England, to see this man, to speak to him if only for a moment, to just generally be in his presence.

He had become scientific royalty, in spite of his crimes against the church. And when he died, he was memorialized thus, in a Westminster Abbey funeral and burial. He would have been thrilled to know it, been elated, really, to know that people had thought his life worthy of such an honor, and to know that people believed what he had done for the world had been for its betterment.

No comments:

Post a Comment